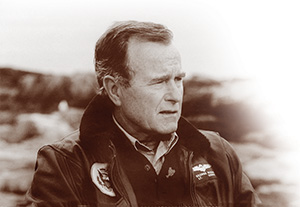

The Last Leader of the Greatest Generation

By William Hanover

Photos by David Valdez

Many declared George Herbert Walker Bush’s death the end of America’s Greatest Generation. A war hero who persevered in times of defeat and dreamed big and whose lone term as the 41st president of the United States saw the end of the Cold War. He formulated a political dynasty for his family that influenced politics for decades.

Many declared George Herbert Walker Bush’s death the end of America’s Greatest Generation. A war hero who persevered in times of defeat and dreamed big and whose lone term as the 41st president of the United States saw the end of the Cold War. He formulated a political dynasty for his family that influenced politics for decades.

“Bush was a figure of an older, fading order of American power,” wrote Bush biographer Jon Meacham in “Dynasty and Power,” a 2015 biography. “When his family and friends looked at him, they saw a man who could have spent his life making and spending money, but who had chosen to obey the biblical injunction, drilled into him by his parents, that to whom much is given much is expected.”

Bush had always felt destined to greatness by his parents. They instilled the notion that life was a contest and winning was its own reward. He saw plenty of defeat losing as many elections as he won. “My motivation’s always been — you know, to be captain,” according to Bush historian Meacham. “Whatever it is. That’s not good in a way, but in a way it is. It’s what motivated me all my life. . . . Whatever you’re in. Be number one.”

Pearl Harbor was enough to convince the young Bush that service called, and considered enlisting in the Royal Canadian Air Force because he thought “you could get through much faster.” He became most say the youngest aviator in the U.S. Navy, flying bombing missions in the Pacific. He was shot down and became a decorated war hero narrowly escaping death and capture. Both his mates perished, and his thoughts about them stayed with him his whole life.

After, he married Barbara Pierce. His wife of 73 years, Barbara Bush, died in April of, 2018, the same year as her husband. At Yale, which Bush completed in two and 1/2 years, he earned Phi Beta Kappa and was the baseball teams’ captain and first baseman.

After his graduation from Yale University in 1948, he was offered a job at his family’s Wall Street investment firm and turned it down and in 1948, in his new Studebaker which was a graduation gift, headed to Texas. He landed in Odessa with their new baby, George. Neil Mallon, a family friend, was the head of Dresser Industries, a leading oilfield equipment company and the young Bush started his career an entry-level sales position with an oilfield tool company.

In 1950 he formed an oil company with backing from his father and some of his father’s friends. With no geologic or engineering background, Bush learned the business from the ground up and later, joined forces with two brothers, Hugh and William Liedtke, to form Zapata Petroleum.

Zapata had raised money and gambled on a field in Coke County that supposedly was “played out.” One of the brothers, Bill Liedtke, had said years later that the young company drilled 130 wells and never had a dry hole.

And his place in history will long be overshadowed, Meacham acknowledges, “by the myth of his predecessor and the drama of his sons.”

Free of scandal or great controversy, with one troubling exception — his role as vice president in the Iran-Contra scandal.

Free of scandal or great controversy, with one troubling exception — his role as vice president in the Iran-Contra scandal.

Bush was the last president to have served in the military during World War II. His experience in international diplomacy helped him well as he dealt with the unraveling of the Soviet Union as an oppressive superpower, and later the rise of China as a commercial behemoth and potential partner.

He spent the next three decades in the political limelight, a career mostly free of scandal or great controversy, with one exception — his role as vice president in the Iran-Contra scandal.

Bush was elected president in 1988 as the successor to Ronald Reagan, a conservative icon whom he ran against and then served as vice president. Unlike Reagan, he was a pragmatic leader guided by moderation, consensus building, and a sense for problem-solving shorn of partisan rhetoric. Like his father, who served in the U.S. Senate, he swore no allegiance to orthodox tenets.

Bush was put to the test shortly after taking office. Surging movements in Eastern Europe saw the opportunity to free themselves from the Soviet yoke, thanks in part to the liberalizing influence of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Bush’s measured response allowed events to unfold, including the destruction of the Berlin Wall, without triggering potentially catastrophic responses from Soviet hard-liners.

Bush again displayed his diplomatic skills in the summer of 1990 when he coordinated a multinational response to the military invasion of tiny Middle East nation Kuwait by neighboring Iraq and its dictator, Saddam Hussein. The victorious Operation Desert Storm brought high approval ratings that appeared to guarantee a second term.

Domestic matters proved a different sort of challenge. Plagued by inherited budget deficits and a Congress under the control of Democrats, Bush was pushed into a tax increase that belied his explicit promise to allow none. He agreed to it because he recognized it was in the country’s best interest, but the political damage was severe. His re-election bid fell short, a failing that haunted him for years. Uncharacteristically, it even caused him to wonder whether history would regard him as a failure.

His place in history may be overshadowed, Meacham acknowledges, “by the myth of his predecessor and the drama of his sons.”

Mostly he was free of scandal or great controversy, with one troubling exception — his role as vice president in the Iran-Contra scandal.

“I think over the years he fares well,” said presidential historian Henry Brands, an author and a professor at the University of Texas. “If voters have a referendum and they vote you down, that automatically puts you down a rung. It’s unfair.”

“The world was fortunate to have his background and instincts at a turning point,” said Robert Gates, who served as Bush’s CIA director and deputy national security adviser. “The collapse and end of the Cold War look sort of pre-ordained in hindsight, but for those who were there, it was not clear how it would happen.”

Gates, who served in eight presidential administrations, suggested that Bush never received the credit he deserved for quietly “greasing the skids” that saw communists slide from power in the Soviet Union.

“There is no precedent in all of history for the collapse of a heavily armed empire without a major war,” Gates said. “He was a figure of enormous historical importance.”

“What’s wrong with trying to help people,” he once asked. “What’s wrong with trying to bring peace? What’s wrong with trying to make the world a little better?”

His one term arguably resulted in more significant legislative achievements than Reagan’s two, among them the Americans with Disabilities Act, a bolstered Clean Air Act, and an increased minimum wage.

He was defeated in an unusual three-way contest with Democrat Clinton and Texas billionaire Ross Perot — a sour coda to a stellar career.